During the pandemic, conferencing software quickly became a required part of work and education culture.

Of course, this technology’s ability to keep us connected has been an important part of keeping people safe, but we’ve also discovered the quirks of this mode of communication. Being bound to this remote interaction inspires curiosity about its potential for collaborative creativity. Musicians have know for a while about the issues of internet latency in coordinating remote ensembles, but what if, instead of attempting to recreate the conditions of a traditional performance in this new medium, we embraced the “space” created by this conferencing software?

In the pieces on this cassette, two analog synthesizers are put into contact via conference software. The audio signal is sent between the two synthesizers, and a feedback loop is created between the two instruments. Feedback loops, such as when we put a microphone close to a speaker, emphasize the resonant frequencies—the imperfections—of a system. As we know, the audio of conferencing software is an imperfect connection, with latency, filtering, and audio compression artifacts.

This conferencing-software feedback loop, then, emphasizes these imperfections, bringing out the character of this communication medium as an emergent soundscape.

All aspects of this cassette embrace this interplay of analog and digital: analog synthesizers, digital feedback loops; pieces were digitally recorded, but mixed with on a hybrid setup with analog EQ and compression; recorded to tape, and also re-digitized for download.

dérive

dérive, Will Klingenmeier’s new ambient album, is glacially symphonic, a melding of lush sonic landscapes. Listening to it, I felt I was hearing rain as it seeped through a mound of jewels and leaves, through flower petals and the spring reverb of a vintage amp. The pieces juxtapose generated sounds and field recordings, and flow together like a river of glass. They serve as a reflection of contemporary interior life filtered through the terms of our shared external reality.

dérive is a collection of three to ten minute pieces pulled from Klingenmeier’s live stream series “Today’s sound is…” These live performances have unfurled for two to three hours apiece in over one hundred episodes (and counting) since September 2020, each one an aural meditation practice, a kind of monastic engagement with the craft of composition. They are laminar flows of sound that turn in upon themselves, both repeating motifs and brachiating into different textures—soothing and complex, subterranean, placid and engaging. As suggested by the title, each piece is connected to a place, to global wandering, and to memory. The album has the same qualities as the original performances—expansive soundscapes that stretch beyond rational time into a continuum of textures, blended and balanced seamlessly so that each cassette side, though a composite, can be heard as a single half-hour composition.

“Today’s sound is…” began in the wake of the Covid-19 lockdowns, during which Klingenmeier was confined to a small living space in Armenia. The pieces help us navigate the quality of simultaneous solitude and remote connection we all migrated to during that time. As a guiding principle of the compositions, Klingenmeier references Brian Eno: “Ambient music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.” I found that to be the case with dérive, and it is as rewarding to listen with full concentration as it is to play it in the background of daily life, reading, housecleaning, cooking, or hanging with friends. I enjoyed the album equally through studio monitors and through a single bluetooth speaker.

The timbres of dérive include statics and hums, saturated guitar distortion, wind and rain, and sounds generated with Kyma, a sound-design system, mediated by performance on a Haken Continuum Fingerboard. There is a blur between field recordings and synthesized elements—Klingenmeier embraces this ambiguity, and notes that it’s sometimes hard to tell which sounds are “natural” and which are tape hiss or noisy guitar. In the blending of analogue and digital signals, and of virtual and natural worlds, dérive serves as a metaphor for contemporary life in which these things are often indistinguishable in our moment to moment reality. As such, with dérive, Klingenmeier has produced a masterpiece of ambient sound composition.

Liner notes by Scott Ezell

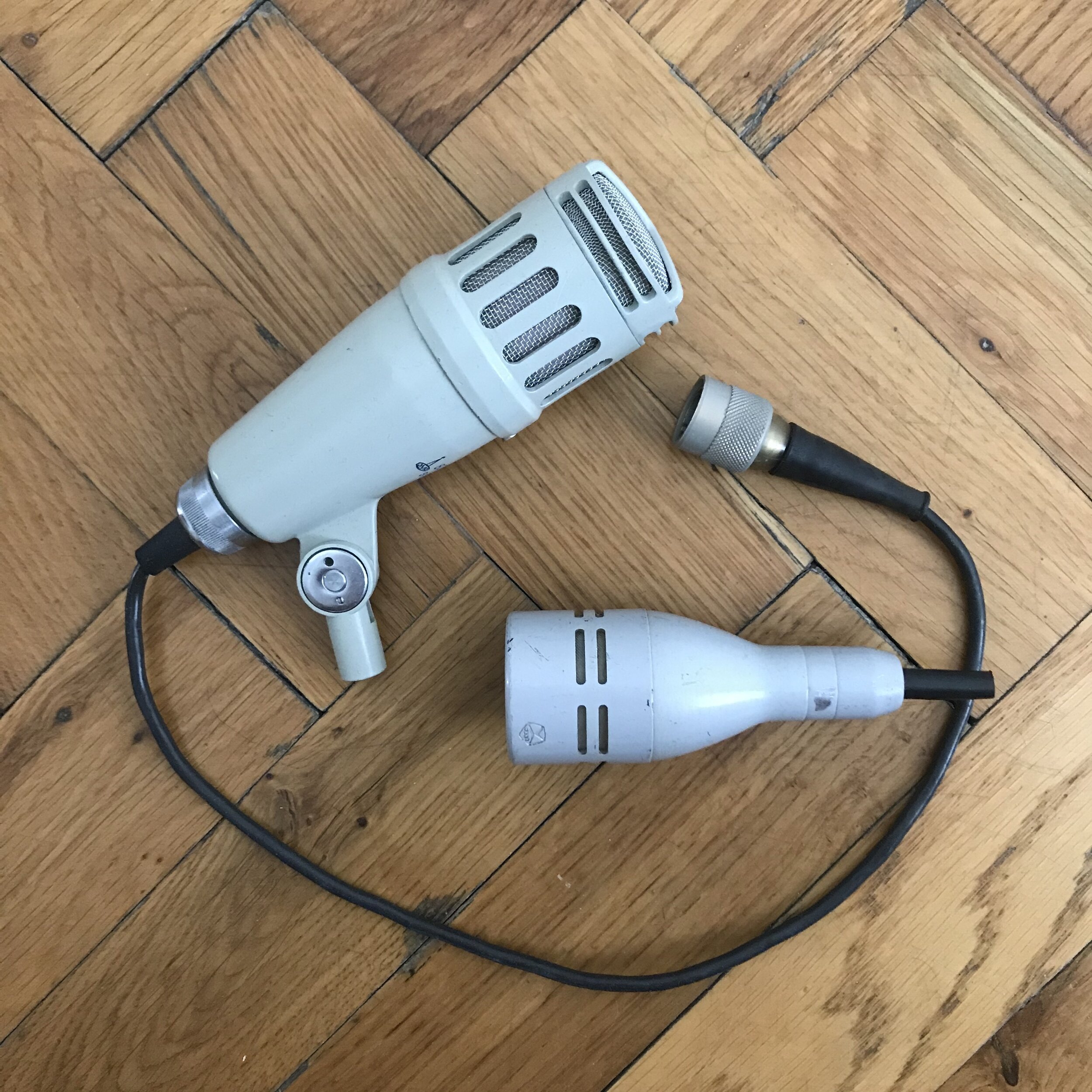

Modernizing and listening to vintage Soviet microphones— LOMO 82A-5M Y2 & Oktava MD-66A

I have finally modernized both the LOMO 82A-5M Y2 and Oktava MD-66A with XLR connections so they can be used in my current recording set-up. In case you’re curious, there is an earlier blog post called ‘Sovetakan Mikrafon’ with some initial thoughts and photographs.

For the LOMO 82A-5M Y2 I ordered two parts. The first was a microphone stand adapter and the second was a 3-pin DIN to XLR both of which I ordered from Russia, paid entirely too much for, and was assured they would be exactly what I needed. Turns out, not quite. The microphone stand adapter worked perfectly but the 3-pin DIN added ground hum indicating that a couple of the pins weren’t soldered the way I needed. I found the Soviet connectors to be exceedingly difficult to use and disassemble for re-soldering so as a result, I went back to the original 3-pin DIN to XLR cable I made and the ground hum disappeared. I only ordered the connector cable from Russia for aesthetic reasons and because I wanted to be able to screw the connectors together. There’s different threading on them than on the connector I made so my homemade cable looks worse, but sounds better.

For the Oktava MD-66A I ordered a foot of Mogami quad-core microphone cable and a XLR connector. Inside the microphone there were two leads and what I figured had to be the ground. Not wanting to spend too much time on something that might not even work, I made an educated guess at the leads for hot (+) and cold (-) (if I got it wrong it’s my understanding that the phase would be flipped) and soldered the three connections. It proved to be more difficult than I expected because the microphone itself had varying hole sizes that I had to feed the microphone cable through. This meant stripping more than I would have liked to of the outermost part of the cable as well as having really long leads going through the microphone up to the point of soldering. At any rate, in the end, what I did worked.

After a year, it’s incredibly exciting to get both of these vintage Soviet microphones working. I made two listening example videos— one for each microphone and I’m thrilled with how they sound, especially the Oktava MD-66A.

A couple of notes for anyone who might find themselves in a similar situation of modernizing vintage (Soviet) microphones. The LOMO 82A-5M Y2 microphone adapter is a peculiar size (2/8” to 5/8”)and you likely won’t find it on Amazon or any other place (I tried and it didn’t fit). Even the adapters that claim to fit vintage mics like AKG etc. aren’t the right size. It seems you need to find an adapter for LOMO specifically, I had to order from Russia for this. Also, be aware that some Soviet gear tightens to the left and loosens to the right— for example a part of my Oktava MD-66A does this. Finally understanding connector pin configuration is critical. Modern 3-pin XLR is pin 1 ground, pin 2 hot (+), pin 3 cold (-). The 3-pin DIN on my LOMO 82A-5M Y2 was different than that and therefore I had to compensate when soldering the connections. The LOMO 82A-5M Y2 connector had small numbers for the pins but there seems to be some variety/inconsistency as the person I bought the parts from had conflicting information to what I researched and personally experienced. As a starting point, here is a link to DIN connectors on wikipedia which might prove to be useful. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DIN_connector

In the end, there’s only 3 pins on these microphones so not too much can go wrong even in a ‘guess and check’ situation. Of course you can be more precise with a voltmeter.

The Front Lines of the War — Chapbook & Cassette

The Front Lines of the War is a spoken word sound art album made with a resonance hum of civil conflict, poetry, and experimental sound.

Scott Ezell published these poems as a collection in August, 2019, based on his first-person experience of a Myanmar military offensive in Shan State, Myanmar. In October 2019 Ezell and Will Klingenmeier collaborated in a performance at the University of California, San Diego, that explored issues of destructive resource extraction and civil war in the China-Southeast Asia border zone. A year later, war broke out between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Artsakh, a contested region where Klingenmeier had volunteered and visited several times. Against the backdrop of this border war, and increasing authoritarianism and civil conflict worldwide, Ezell and Klingenmeier began collaborating on this sound art and spoken word version of The Front Lines of the War. This album is rooted in personal connections to contested landscapes and marginalized communities, as it explores the ways that global systems implicate us all in vectors of destruction and conflict, in which “everyone is on the front lines of the war.”

As a coda to the original collection, the album includes a section from a later poem-cycle, “Heat Maps,” based on Richard Mosse’s conceptual documentary photos of displaced persons and refugee camps.

On February 1, 2021 the Myanmar military launched a coup, jailing democratically elected leaders and sending militarized police into the streets and countryside. Air and ground offensives against civilians have continued until today, and despite international condemnation and a nationwide uprising against the coup, regional powers including China and Thailand have continued to support the Myanmar military. Tragically, hundreds of protesters, including a number of young Burmese poets dissenting against the coup, have been killed by the military. This on-going humanitarian tragedy sadly gives “The Front Lines of the War” added significance as an expression of opposition to authoritarian police state rule, in Myanmar and beyond.

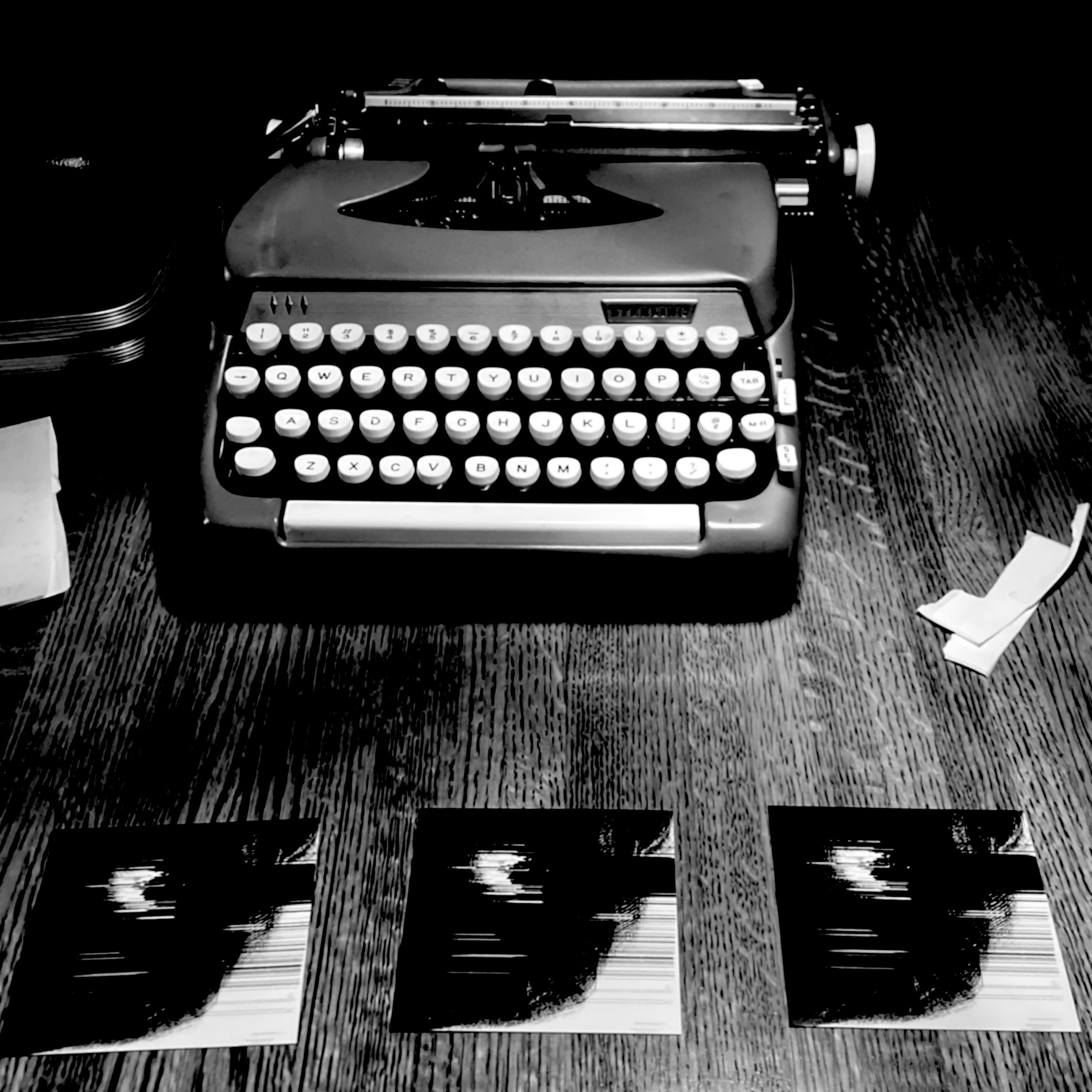

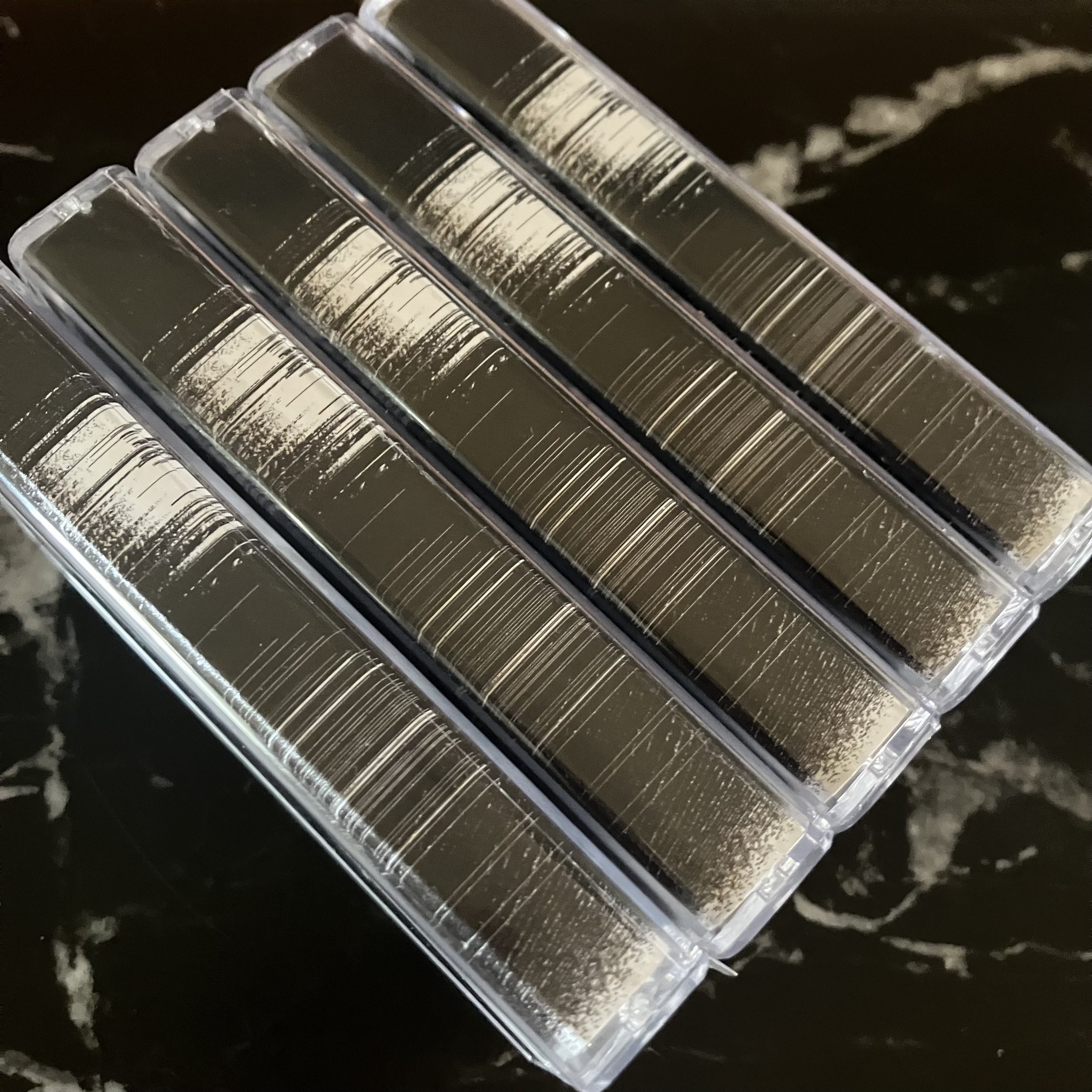

The Front Lines of the War is being released as a limited edition cassette box set, as well as being available for digital streaming and download. The box set includes the 60-minute cassette, a re-release of the original chapbook “The Front Lines of the War,” as well as hand-made materials and inserts. The coda is included as a special edition, hand-printed on natural fiber paper by an indigenous women’s collective in Chiapas, Mexico, and numbered certification cards were typed on a vintage Olivetti typewriter. Protective cassette boxes have been individually processed with a unique distressing method, which parallels the element of randomness and glitching that is central to the production ethos of the album.

Databending, a form of glitch art, is a process in which a file is deliberately altered or damaged. This disruption is integral to the album in the way it signifies the fundamental disruption of human lives and natural ecosystems through war and conflict. Glitching introduces elements of randomness and improvisation which allow chance and surprise to become part of a creative process. The Front Lines of the War mirrors the increasing chance and randomness of life for marginalized peoples, and the ability to adjust and improvise which are necessary elements of resilience.

The final sound was realized entirely in Symbolic Sound’s real-time sound design language, Kyma. In two unique performances, one for each side of the album, the individual Kyma-created track structures were recombined and concatenated.

The album was mastered by Taylor Deupree at 12k in Pound Ridge, New York.

The album will also be available for digital download and streaming on Spotify, iTunes, YouTube, and other streaming platforms.

Scott Ezell is a poet and multi-genre artist with a background in Asia, border zones, and indigenous peoples.

An omnivore of sound, lover of monophonic plainchants, noise, and the dérive, Will Klingenmeier has spent the last fifteen years living as a borderline hermit developing a distinct sonic palate. He is a sound artist placing emphasis on indeterminacy, code, field recordings and synthesis.

For more information contact Scott or Will:

Sovetakan Mikrafon →

A daily search for soviet era microphones in Armenia

For the last 6 months I’ve been in Armenia with a lot of creative time on my hands. As such, I’ve started living like a local which has lead me to perusing the classified ads my best friend introduced me to. Initially, this was to find a musical instrument to play during the lockdown, but it quickly lead to a daily search for obscure, soviet era microphones.

As a former part of the USSR, Armenia has tons of soviet era objects around, from defunct bus stops to vintage microphones. To date, I’ve been able to find two microphones that really caught my eye: the Lomo 82A-5M Y2 and Oktava MD-66A, both of which will need a bit of modernization before they are useable in my current recording rig but they look promising.

I’ll write again once I have recorded with them.

Yerevan in Rain →

A reminder to do what I can, with what I have, where I am, while I embrace my circumstances…

It’s the last day of April 2020—for a month and a half now I’ve been sequestered in an apartment in Yerevan, Armenia after my plans to volunteer at TUMO were disrupted by the COVID-19 lockdown. In the space since March, I’ve observed the sonic cityscape evolve from human noise pollution to bird symphonies and I’ve creatively documented it along the way through sounds and visuals. Some images are included here while the sounds will come later.

Admittedly, I’ve been incredibly fortunate in this lockdown, I’ve always been an introvert, I’ve always been delighted to be by myself, and I’ve always been bored to tears with politics and news, so letting the latter pass me by while I was obligated to be alone was essentially what I would have been doing anyway. With my family and friends safe all I could do was work on myself.

That said, there were some obstacles but what I found is that they weren’t the obvious ones I thought they were initially—instead they were assumptions in my head—assumptions that I didn’t have the right equipment to do the things I wanted. In fact, there were several instances where I thought I couldn’t do something because of physical resource limitations and as it turns out I could do them all with what I had on hand, and I finally did.

The specifics of these cases don’t matter, what does matter is realizing that you should do the best you can, with what you have, where you are, while accepting your current circumstances rather than rejecting them. And there’s always a way; restraint breeds creativity. What’s more, I found it important to remind myself that I’m solely responsible for my experience in the world—I may not be able to control what happens to me but I can control my reaction to it. So on the other side of this, even now, I’m working to be better than I was before.